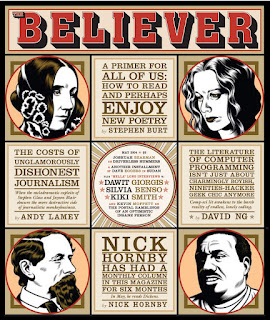

Field reportage had long been an element of the publications that Egger s edited or published, not least in The Believer itself arts writing cutting political field reporting to Might magazine -- turning in a sharp critique on how the antiwar protests that spring might have proved to be "more about voicing opposition for the record than actually affecting the chances for a war."

But "It Was Just Boys Walking" represented a new commitment to that form by Eggers himself in his work. It's written very much in the vein of modern longform journalism: a sharply described opening in a deafeningly loud cargo plane, followed by a section of back-story person

The first and third installments are essentially straight-up "New New Journalism" -- something that would be perfectly at home in the New Yorker. The second installment, curiously, is an oral history by Deng -- also a well-established form itself, and one that we'll soon see taking particular significance here in the McSweeney's subsequent Voice of Witness publications.

What's structurally interesting about this piece, though, is that Eggers inserted an oral history squarely into longform journalistic narrative -- a